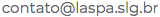

Arte como tecno-encantamento (Gell 1994)

[The art of Kula (Shirley F. Campbell. 2002. The art of Kula. Oxford: Berg, p.115)]

GELL. Alfred. 1994. The technology of enchantment and the enchantment of technology. In: Jeremy Coote; Anthony Shelton (eds.). Anthropology, art and aesthetics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp.40-63.

ANTROPOLOGIA como SOLVENTE DE INSTITUIÇÕES

But this willingness to place ourselves under the spell of all manner of works of art […] is paradoxically the major stumbling-block in the path of the anthropology of art, the ultimate aim of which must be the dissolution of art, in the same way that the dissolution of religion, politics, economics, kinship, and all other forms under which human experience is presented to the socialized mind, must be the ultimate aim of anthropology in general. (Gell 1994:40-1)

ATEÍSMO METODOLÓGICO

It seems to me incontrovertible that the anthropological theory of religion depends on what has been called by Peter Berger ‘methodological atheism’ (Berger, 1967: 107). This is the methodological principle that, whatever the analyst’s own religious convictions, or lack of them, theistic and mystical beliefs are subjected to sociological scrutiny on the assumption that they are not literally true. Only once this assumption is made do the intellectual manreuvres characteristic of anthropological analyses of religious systems become possible, that is, the demonstration of linkages between religious ideas and the structure of corporate groups, social hierarchies, and so on. Religion becomes an emergent property of the relations between the various elements in the social system, derivable, not from the condition that genuine religious truths exist, but solely from the condition that societies exist. […] The consequences of the possibility that there are genuine religious truths lie outside the frame of reference of the sociology of religion. These consequences – philosophical, moral, political, and so on – are the province of the much longer-established intellectual discipline of theology […]. […] I would suggest that the study of aesthetics is to the domain of art as the study of theology is to the domain of religion. That is to say, aesthetics is a branch of moral discourse which depends on the acceptance of the initial articles of faith: that in the aesthetically valued object there resides the principle of the True and the Good, and that the study of aesthetically valued objects constitutes a path toward transcendence. […] [T]hat would present no problem even to non-atheists, simply because nobody expects a sociologist of religion to adopt the premises of the religion he discusses; indeed, he is obliged not to do so. (Gell 1994:41-2)

FILISTINISMO METODOLÓGICO

The equivalent of methodological atheism in the religious domam would, in the domain of art, be methodological philistinism […]. Methodological philistinism consists of taking an attitude of resolute indifference towards the aesthetic value of works of art – the aesthetic value that they have, either indigenously, or from the standpoint of universal aestheticism. Because to admit this kind of value is equivalent to admitting, so to speak, that religion is true, and just as this admission makes the sociology of religion impossible, the introduction of aesthetics (the theology of art) into the sociology or anthropology of art immediately turns the enterprise into something else. (Gell 1994:42)

[T]he first step which has to be taken in devising an anthropology of art is to make a complete break with aesthetics. Just as the anthropology of religion commences with the explicit or implicit denial of the claims religions make on believers, so the anthropology of art has to begin with a denial of the claims which objects of art make on the people who live under their spell, and also on ourselves, in so far as we are all self-confessed devotees of the Art Cult. (Gell 1994:42)

ARTE como SISTEMA TÉCNICO para OBTENÇÃO DE AQUIESCÊNCIA pelo ENCANTAMENTO

We recognize works of art, as a category, because they are the outcome of technical process, the sorts of technical process in which artists are skilled. […] There seems every justification, therefore, for considering art objects initially as those objects which demonstrate a certain technically achieved level of excellence, ‘excellence’ being a function, not of their characteristics simply as objects, but of their characteristics as made objects, as products of techniques. (Gell 1994:43)

I consider the various arts – painting, sculpture, music, poetry, fiction, and so on – as components of a vast and often unrecognized technical system, essential to the reproduction of human societies, which I will be calling the technology of enchantment. In speaking of ‘enchantment’ I am making use of a cover-term to express the general premiss that human societies depend on the acquiescence of duly socialized individuals in a network of intentionalities whereby, although each individual pursues (what each individual takes to be) his or her own self interest, they all contrive in the final analysis to serve neccessities which cannot be comprehended at the level of the individual human being, but only at the level of collectivities and their dynamics. As a first approximation, we can suppose that the art-system contributes to securing the acquiescence of individuals in the network of intentionalities in which they are enmeshed. […] [A]rt […] is propaganda on behalf of the status quo (Gell 1994:43)

[A]rt provides one of the technical means whereby individuals are persuaded of the necessity and desirability of the social order which encompasses them (Gell 1994:44)

As a technical system, art is orientated towards the production of the social consequences which ensue from the production of these objects. The power of art objects stems from the technical processes they objectively embody: the technology of enchantment is founded on the echantment of technology. The enchantment of technology is the power that technical processes have of casting a spell over us so that we see the real world in an enchanted form. Art, as a separate kind of technical activity, only carries further, through a kind of involution, the enchantment which is immanent in all kinds of technical activity. (Gell 1994:44)

EFICÁCIA SIMBÓLICA DA PRANCHA TROBRIAND RESIDE NA HABILIDADE TECNOMÁGICA IMPUTADA AO ESCULTOR E NO PRESTÍGIO ATRIBUÍDO AO SEU PROPRIETÁRIO

The canoe-board is a potent psychological weapon […]. Its efficacy is to be attributed to the fact that these disturbances, mild in themselves, are interpreted as evidence of the magical power emanating from the board. It is this magical power which may deprive the spectator of his reason. […] It is the fact that an impressive canoe-board is a physical token of magical prowess on the part of the owner of the canoe which is important, as is the fact that he has access to the services of a carver whose artistic prowess is also the result of his access to superior carving magic. (Gell 1994:46)

The Halo-Effect of Technical ‘Difficulty’ […] And this leads on to the main point that I want to make. It seems to me that the efficacy of art objects as components of the technology of enchantment – a role which is particularly clearly displayed in the case of the Kula canoe – is itself the result of the enchantment of technology, the fact that technical processes, such as carving canoe-boards, are construed magically so that, by enchantmg us, they make the products of these technical processes seem enchanted vessels of magical power. That is to say, the canoe-board is not dazzling as a physical object, but as a display of artistry explicable only in magical terms, something which has been produced by magical means. It is the way an art object is construed as having come into the world which is the source of the power such objects have over us – their becoming rather than their being. (Gell 1994:46)

Here the technology of enchantment and the enchantment of technology come together. The matchstick model, functioning essentially as an advertisement, is part of a technology of enchantment, but it achieves its effect via the enchantment cast by its technical means, the manner of its coming into being, or, rather, the idea which one forms of its coming into being (Gell 1994:47)

O PODER DA OBRA DE ARTE

I think that the peculiar power of works of art does not reside in the objects as such, and it is the objects as such which are bought and sold. Their power resides in the symbolic processes they provoke in the beholder, and these have sui generis characteristics which are independent of the objects themselves and the fact that they are owned and exchanged. (Gell 1994:48)

RESISTÊNCIA INTELECTUAL e IMPUTAÇÃO DE MAGIA

The resistance which they offer, and which creates and sustains this desire, is to being possessed in an intellectual rather than a material sense, the difficulty I have in mentally encompassing their coming-into-being as objects in the world accessible to me by a technical process which, since it transcends my understanding, I am forced to construe as magical. (Gell 1994:49)

O MILAGRE HUMANO DA TÉCNICA

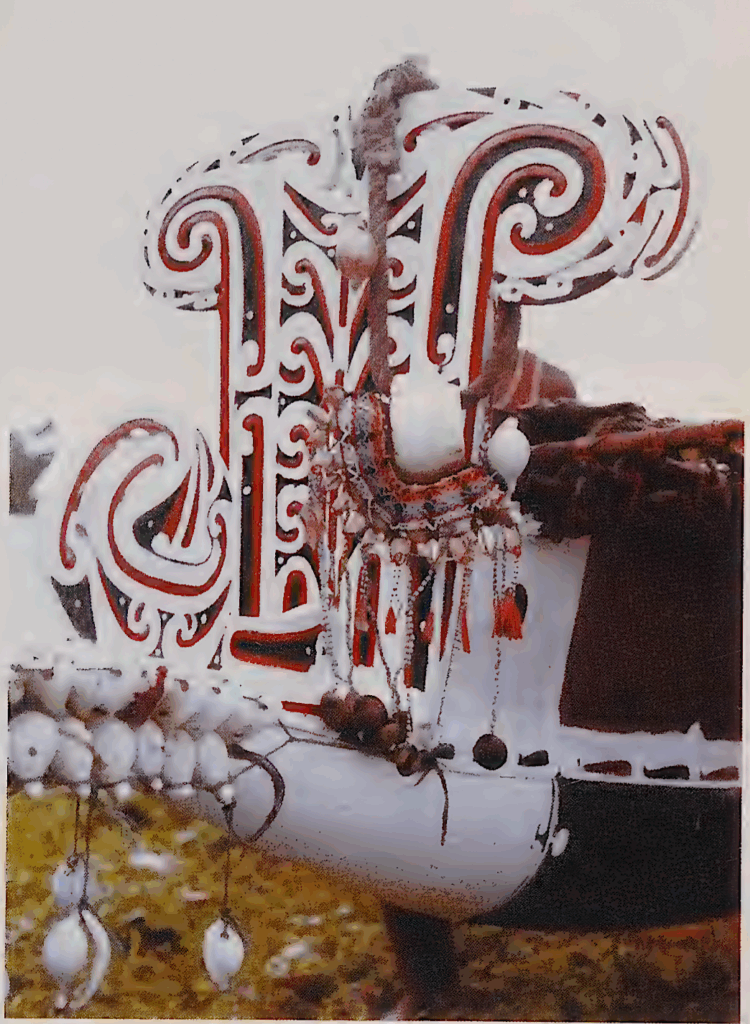

The painting’s power to fascinate stems ennrely from the fact that people have great difficulty in working out how coloured pigments (substances with which everybody is broadly familiar) can be applied to a surface so as to become an apparently different set of substances, namely, the ones which enter into the composition of letters, ribbons, drawing-pins, stamps, bits of string, and so on. […] This technical miracle must be distinguished from a merely mysterious process: it is miraculous because it is achieved both by human agency but at the same time by an agency which transcends the normal sense of self-possession of the spectator. (Gell 1994:49)

[Old time letter rack (John F. Peto 1894)]

PINTURA x FOTOGTAFIA

[T]he letter rack picture [pintura de John Peto] would not have the prestige it does have if it were a photograph, visually identical in colour and texture […]. Its prestige depends on the fact that it is a painting; and, in general, photography never achieves the popular prestige that painting has in societies which have routinely adopted photography as a technique for producing images. This is because the technical processes involved in photography are articulated to our notion of human agency in a way which is quite distinct from that in which we conceptualize the technical processes of painting, carving, and so on. The alchemy involved in photography (in which packets of film are inserted into cameras, buttons are pressed, and pictures of Aunt Edna emerge in due course) are regarded as uncanny, but as uncanny processes of a natural rather than a human order, like the metamorphosis of caterpillars into butterflies. The photographer, a lowly button-presser, has no prestige, or not until the nature of his photographs is such as to make one start to have difficulties conceptualizing the processes which made them achievable with the familiar apparatus of photography. […] In societies which are not over-familiar with the camera as a technical means, the situation is, of course, quite different. (Gell 1994:49-50)

O IMPACTO DA OBRA DERIVA DO DESCOMPASSO ENTRE AS HABILIDADES DO ESPECTADOR E DO ARTISTA

The point I wish to establish is that the attitude of the spectator towards a work of art is fundamentally conditioned by his notion of the technical processes which gave rise to it, and the fact that it was created by the agency of another person, the artist. The moral significance of the work of art arises from the mismatch between the spectator’s internal awareness of his own powers as an agent and the conception he forms of the powers possessed by the artist. In reconstructing the processes which brought the work of art into existence, he is obliged to posit a creative agency which transcends his own and, hovering in the background, the power of the collectivity on whose behalf the artist exercised his technical mastery. (Gell 1994:51-2)

ARTE é INERENTEMENTE SOCIAL

The work of art is inherently social in a way in which the merely beautiful or mysterious object is not: it is a physical entity which mediates between two beings, and therefore creates a social relation between them, which in turn provides a channel for further social relations and influences. (Gell 1994:52)

CRIANDO ASSIMETRIAS ENTRE PESSOAS PELAS SUAS RELAÇÕES COM COISAS

[T]echnical virtuosity is intrinsic to the efficacy of works of art in their social context, and tends always towards the creation of asymmetries in the relations between people by placing them in an essentially asymmetrical relation to things. (Gell 1994:52)

[Baboon and young (Pablo Picasso 1951)]

ALQUIMIA ESSENCIA DA ARTE

the essential alchemy of art, which is to make what is not out of what is, and to make what is out of what is not. (Gell 1994:53)

O VALOR DA DIFICULDADE

The kind of technical sophistication involved is not the technology of illusionism but the technology of the radical transformation of materials, in the sense that the value of works of art is conditioned by the fact that it is difficult to get from the materials of which they are composed to the finished product. If we take up the example of the Trobriand canoe-board once more, it is clear that it is very difficult to acquire the art of transforming the root-buttress of an ironwood tree, using the rather limited tools which the Trobrianders have at their disposal, into such a smooth and refined finished product. If these boards could be simply cast in some plastic material, they would not have the same potency, even though they might be visually identical. (Gell 1994:54)

HOMOLOGIA SOCIOTÉCNICA

[I]t is not the eye-spots or the visual instabilities which fascinate, but the fact that it lies within the artist’s power to make things which produce these striking effects. We can now see that the technical activity which goes into the production of a canoe-board is not only the source of its prestige as an object, but also the source of its efficacy in the domain of social relations; that is to say, there is a fundamental scheme transfer, applicable, I suggest, in all domains of art production, between technical processes involved in the creation of a work of art and the production of social relations via art. In other words, there exists a homology between the technical processes involved in art, and technical processes generally, each being seen in the light of the other, as, in this instance, the technical process of creating a canoe-board is homologous to the technical processes involved in successful Kula operations. (Gell 1994:56)

SOCIEDADE como EFEITO DA INFRAESTRUTURA TÉCNICA

Art production and the production of social relations are linked by a fundamental homology: but what are social relations? Social relations are the relations which are generated by the technical processes of which society at large can be said to consist, that is, broadly, the technical processes of the production of subsistence and other goods, and the production (reproduction) of human beings by domesticating them and breeding them. Therefore, in identifying a homology between the technical processes of art production and the production of social relations, I am not trying to say that the technology of art is homologous to a domain which is not, itself, technological, for social relations are themselves emergent characteristics of the technical base on which society rests. (Gell 1994:57)

AGRICULTURA (conhecimento, habilidade e incerteza)

Three things stand out when one considers the technical activity of gardening: firstly, that it involves knowledge and skill, secondly, that it involves work, and thirdly, that it is attended by an uncertain outcome, and moreover depends on ill-understood processes of nature. Conventional wisdom would suggest that what makes gardening count as a technical activity is the aspect of gardening which is demanding of knowledge, skill, and work, and that the aspect of gardening which causes it to be attended with magical rites, in pre-scientific societies, is the third one, that is its uncertain outcome and ill-understood scientific basis. (Gell 1994:57)

MAGIA e INCERTEZA

The idea of magic as an accompaniment to uncertainty does not mean that it is opposed to knowledge, i.e. that where there is knowledge there is no uncertainty, and hence no magic. On the contrary, what is uncertain is not the world but the knowledge we have about it. One way or another, the garden is gomg to turn out as it turns out; our problem is that we don’t yet know how that will be. All we have are certain more-or-less hedged beliefs about a spectrum of possible outcomes, the more desirable of which we will try to bring about by following procedures in which we have a certain degree of belief, but which could equally well be wrong, or inappropriate in the circumstances. The problem of uncertainty is, therefore, not opposed to the notion of knowledge and the pursuit of rational technical solutions to technical problems, but is inherently a part of it. If we consider that the magical attitude is a by-product of uncertainty, we are thereby committed also to the proposition that the magical attitude is a by-product of the rational pursuit of technical objectives using technical means. (Gell 1994:57)

MAGIA COMO PADRÃO DE VALOR

The standard for computing the value of a harvest is the opportunity cost of obtaining the resulting harvest, not by the technical, work-demanding means that are actually employed, but effortlessly, by magic. All productive activities are measured against the magic-standard, the possibility that the same product might be produced effortlessly, and the relative efficacy of techniques is a function of the extent to which they converge towards the magic-standard of zero work for the same product […]. […] If there is any truth in this idea, then we can see that the notion of magic, as a means of securing a product without the work-cost that it actually entails, using the prevailing technical means, is actually built into the standard evaluation which is applied to the efficacy of techniques, and to the computation of the value of the product. Magic is the baseline against which the concept of work as a cost takes shape. (Gell 1994:58)

TRABALHO e MAGIA

Magic haunts technical activity like a shadow; or, rather, magic is the negative contour of work, just as, in Saussurean linguistics, the value of a concept (say, ‘dog’) is a function of the negative contour of the surrounding concepts (‘cat’, ‘wolf, ‘master’). (Gell 1994:59)

DINHEIRO e MAGIA

Just as money is the ideal means of exchange, magic is the ideal means of technical production. And just as money values pervade the world of commodities, so that it is impossible to think of an object without thinking at the same time of its market price, so magic, as the ideal technology, pervades the technical domain in pre-scientific societies. (Gell 1994:59)

FETICHISMO DA MERCADORIA

In technologically advanced societies where different technical strategies exist, […] the situation is different, because different technical strategies are opposed to one another, rather than being opposed to the magic-standard. But the technological dilemmas of modem societies can, in fact, be traced to the pursuit of a chimera which is actually the equivalent of the magic-standard: ideal ‘costless’ production. This is actually not costless at all, but the minimization of costs to the corporation by the maximization of social costs which do not appear on the balance sheet, leading to technically generated unemployment, depletion of unrenewable resources, degradation of the environment, etc. (Gell 1994:62 nota 3)

TECNOLOGIA MÁGICA

What I want to suggest is that magical technology is the reverse side of productive technology, and that this magical technology consists of representing the technical domain in enchanted form. (Gell 1994:59)

JARDIM TROBRIAND

The Trobriand garden is, therefore, both the outcome of a certain system of technical knowledge and at the same time a collective work of art, which produces yams by magic. (Gell 1994:60)

PRIMITIVO-MODERNO

I hope the reader will accept the use of ‘primitive’ in a neutral, non-derogatory sense in the context of this essay. It is worth pointing out that the Trobriand carvers who produce the primitive art discussed in this essay are not themselves at all primitive; they are educated, literate in various languages, and familiar with much contemporary technology. They continue to fabricate primitive art because it is a feature of an ethnically exclusive prestige economy which they have rational motives for wishing to preserve. (Gell 1994:62 nota 1)

LaSPA is located at the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences (

LaSPA is located at the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences (